Lughnasadh, sometimes called Lammas, is the first of the harvest festivals in the Pagan Wheel of the Year. Celebrated around August 1st, it marks the start of the grain harvest and a time to reflect on the fruits of your labour, honouring the land, and taking stock of what has been sown and reaped — literally and symbolically.

Rooted in Celtic tradition, Lughnasadh is named for one of the most important gods of the Irish pantheon: Lugh of the Long Arm (Lugh Lámhfhada). From baking bread to lighting ritual fires, let’s look at the deeper meaning of this ancient tradition and how to celebrate it in modern, meaningful ways.

WHAT IS LUGHNASADH?

Lughnasadh (pronounced LOO-nah-sah) is one of the eight festivals of the Pagan Wheel of the Year. It marks the beginning of the harvest season — particularly the grain harvest — and is associated with gratitude, skill, sacrifice, and abundance themes.

WHO IS LUGH?

In Irish mythology, Lugh is a solar-aligned deity, but more than just a sun god. He’s a warrior, king, craftsman, poet, musician, and master of every art.

According to the mythological cycle of medieval Irish literature, Lugh gained entry to the court of the Tuatha Dé Danann by proving he could do everything — from smithing and carpentry to magic and strategy. As a result, he was often called Samildánach, meaning "skilled in all arts."

Lugh is also the slayer of Balor of the Evil Eye, his own tyrannical grandfather, in the mythic battle of Mag Tuired — a tale rich with archetypes of sacrifice, renewal, and the reclaiming of divine order.

The name Lugh (or Lug) appears often in early Irish texts, but its exact origin is still debated. One older theory connects it to the Proto-Indo-European root leuk-, meaning “light” or “brightness,” which would suggest a link to the sun or radiance.

However, many modern linguists favour a different origin — the root lewgh-, which means “to swear an oath” or “to bind by vow.” This interpretation places Lugh not simply as a solar deity, but as a divine figure of contract, honour, and responsibility — a god who embodies the sacredness of one’s word and the skill to uphold it.

A FUNERAL, NOT A FEAST?

Interestingly, Lughnasadh was established initially not to glorify Lugh himself, but to honour his foster-mother, the goddess Tailtiu. According to the Book of Invasions (Lebor Gabála Érenn), Tailtiu died from exhaustion after clearing the land at Tailten for agriculture. Her death is remembered as an act of sacrifice, symbolising the labour and loss often hidden behind the shaping of the land and, by extension, the foundations of society itself.

In her memory, Lugh instituted funeral games and gatherings, known as the Óenach Tailten, held at Teltown (Tailtin) in County Meath. These included:

-

Competitive athletic contests (like the ancient Irish equivalent of the Olympics)

-

Horse races, music, and storytelling

- Market fairs

- Handfastings — temporary unions or trial marriages, often lasting “a year and a day” after which the couple might choose to stay together or part ways without dishonour.

This was a time for tribal gathering, peacemaking, and honouring the land and the dead, not unlike what we see in other ancient harvest rites from across Europe.

HOW DO WE KNOW ABOUT LUGHNASADH?

Evidence of Lughnasadh comes from a mix of:

-

Medieval Irish texts (e.g., Lebor Gabála Érenn, Cath Maige Tuired)

-

Place names (e.g., Tailtin / Teltown)

-

Archaeological sites that hosted ancient games and fairs

- Folklore and customs recorded by 18th- and 19th-century scholars.

Though much of it was later reframed through Christian and colonial lenses, the core themes — harvest, gratitude, craftsmanship, and remembrance — endure.

WHO CELEBRATED LUGHNASADH?

Originally, Celtic peoples across Ireland and parts of Britain would have observed some form of Lughnasadh. Over time, regional variations developed:

-

In Scotland, it became Lùnastal.

-

In Wales, the first harvest is sometimes linked to Gŵyl Awst.

- Anglo-Saxons adopted a Christianized version called Lammas (Loaf Mass).

Today, modern Pagans, Druids, Wiccans, and reconstructionists celebrate Lughnasadh as a living festival, not just a relic of the past, but a vital part of their spiritual calendar.

WHAT IS LAMMAS? A LOAF FOR THE LORD

While Lughnasadh has its roots in ancient Celtic mythology, Lammas (short for “Loaf Mass”) emerged later as a Christian harvest festival observed in the British Isles. Falling on August 1st, Lammas marked the offering of the first loaf of bread made from the newly harvested grain — a ritual of thanksgiving, tithing, and divine blessing.

LAMMAS FESTIVAL MEANING

The name Lammas comes from the Old English hlāfmæsse, “loaf-mass.” In medieval England, a farmer baked his first wheat into a loaf and set it on the church altar as a quiet thank-you for the coming crop. It echoed older first-fruit customs, where the earliest and finest of the harvest went back to God and the wider community. By doing so, they hoped to secure divine favour for the rest of the harvest season.

Where Lughnasadh honoured Lugh and the land, Lammas sanctified the crop through the Church.

LAMMAS IN MEDIEVAL AND ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

In Anglo-Saxon England, Lammas held both legal and religious importance. It was one of the quarter days that divided the farming year. It was when rents were paid, leases renewed, and land often changed hands. The loaf offered at Lammas wasn’t just a religious gesture — it was part of the practical rhythm of rural life, tied to both the church and the customs of the land.

You’ll still find traces of it in British place names:

-

Lammas Land in Cambridge, used for grazing after harvest

- Lammas Fair in Ballycastle, Northern Ireland — now more about sweets and stalls than sacred bread, but the threads remain.

LAMMAS RITUALS AND FOLK TRADITIONS

Although Lammas was a Christianised version of earlier Pagan rites, it retained many folk customs with clear pre-Christian roots, including:

-

Reaping rituals and corn dollies (straw figures made from the last sheaf)

-

Bonfires and community feasts

- Protective charms made from grain and hung in the home.

Over time, Lammas and Lughnasadh became entangled — sometimes synonymous, sometimes side by side. One in honour of the land and gods, the other in gratitude to the Christian deity — both echoing the same fundamental truth:

We harvest not just to survive, but to give thanks, remember, and belong.

LAMMAS VS LUGHNASADH: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

Today, most modern Pagans blend the traditions of Lughnasadh and Lammas, drawing from the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon roots of the early August harvest festival. While the names are sometimes used interchangeably, the choice of term often reflects a person’s specific tradition or spiritual focus.

-

Reconstructionist Pagans, such as Celtic polytheists, Druids, or followers of Irish or Gaelic traditions, are more likely to use the term Lughnasadh and focus on honouring the god Lugh, the legacy of Tailtiu, and historically rooted practices.

- Wiccans, eclectic Pagans, and those working within Anglo-centric or blended traditions may prefer the name Lammas, especially when emphasising the symbolism of bread, grain, and seasonal gratitude.

In practice, many modern pagan celebrations include elements from both — baking bread, making offerings to deities or the land, decorating with wheat and sunflowers, or holding small fire rituals. Whether you call it Lughnasadh or Lammas, the heart of the observance remains the same: a time to honour effort, recognise growth, and give thanks for what sustains us.

For Christian or folk practitioners, Lammas may be kept as a simple day of gratitude, with bread and blessings shared among family, friends, or the wider community.

WEAR YOUR DEVOTION WITH JEWELLERY ROOTED IN PAGAN HISTORY

THE FIRST PAGAN HARVEST FESTIVAL IN THE WHEEL OF THE YEAR

Lughnasadh is the first of the three Pagan harvest festivals, followed by Mabon (Autumn Equinox) and Samhain (the final harvest and ancestral feast). It holds a vital place on the Wheel of the Year, the modern Pagan calendar that maps the solar cycle through eight seasonal sabbats.

Falling at the cross-quarter point between the Summer Solstice (Litha) and Autumn Equinox (Mabon), Lughnasadh marks the beginning of the waning half of the year.

A FIRE FESTIVAL OF GRATITUDE AND SACRIFICE

Though Lughnasadh celebrates the first fruits of the harvest, it is also one of the four Celtic fire festivals, alongside:

-

Imbolc (early spring)

-

Beltane (May Day)

- Samhain (end of the harvest and the year).

Like its fiery siblings, Lughnasadh uses flame as a ritual force to honour the sun god Lugh, offer up the season’s bounty, and purify what must be let go before the darker days begin.

Bonfires were traditionally lit on high ground, drawing communities together for feasting, games, and offerings to the gods and spirits of the land. At Lughnasadh, fire serves as a focal point for celebration and a symbol of transformation and release — burning away what is no longer needed, marking sacrifice, and honouring the lingering strength of the sun as the year begins its slow turn toward autumn.

LUGHNASADH IN THE WHEEL OF THE YEAR

The Wheel of the Year Lughnasadh stands opposite Imbolc, the festival of potential and early stirrings of life. Where Imbolc asks us to plant, Lughnasadh asks us to reap — not just in crops, but in personal growth, spiritual lessons, creative work, and hard-earned wisdom.

It’s a powerful time to:

-

Reflect on the fruits of your labour

-

Celebrate skills, craftsmanship, and effort.

-

Give thanks for abundance, and share it.

- Prepare for what must be stored, preserved, or surrendered.

Summer begins its shift. The days are still warm, but the light has changed — softer, lower, edged with the first hints of autumn. This is a time between work and rest, growth and decline. There’s a weight to the air, and a sense that the land is beginning to slow — not yet finished, but no longer rising.

EXPLORE KNOTWORK AND SACRED SYMBOLS IN OUR CELTIC AND NORSE ART BOOKS

HOW TO CREATE A LUGHNASADH FIRE RITUAL

As one of the four traditional Celtic fire festivals, Lughnasadh invites a connection with fire as a physical element and a symbol of renewal and change. Whether you live deep in the countryside or in a city flat, you can still honour Lugh’s spirit and the harvest season through a simple fire ritual that blends ancient themes with modern practice.

STEP-BY-STEP: YOUR LUGHNASADH FIRE RITUAL

You don’t need a blazing bonfire or a druidic stone circle to mark the season — though if you have one, by all means, use it. Here’s a simple way to create a meaningful Lughnasadh fire ritual, outdoors or at home.

1. PREPARE YOUR SPACE

Choose a safe place for your ritual:

-

Outdoors: Use a fire pit, cauldron, or small bonfire

- Indoors: Use a fireproof bowl or a large candle (orange, gold, or red are traditional harvest colours).

Cleanse the area with herbs like rosemary or mugwort, or simply by sweeping and setting a clear intention.

2. GATHER SEASONAL OFFERINGS

Offer what you have grown or created, such as:

-

A small loaf of bread or a grain bundle

-

Fresh herbs, berries, or wildflowers

- A handwritten note listing what you’ve achieved or learned since Imbolc or Beltane.

You can also include a symbolic item to burn, such as a slip of paper with something you wish to release.

Write down one harvest (a win) and one thing to let go (a weight).

3. CALL THE FIRE

Light your fire or candle with a spoken intention. Example:

“I light this fire in honour of the harvest of grain, labour, and wisdom. May the flames carry my gratitude, and burn away what I no longer need.”

You may also wish to call upon Lugh, the sun, or your own guides or deities.

4. MAKE THE OFFERING

Place your offerings near or into the fire (safely) one by one. You might say:

-

“For what I have achieved, I give thanks.”

-

“For what I release, I let go with trust.”

- “For what is yet to come, I make space.”

Let the flames transform your intentions. Sing, drum, or sit in quiet reflection.

5. CLOSE THE RITUAL

When you’re ready, extinguish the fire or candle respectfully. Thank the flame, the land, and any deities or spirits you invoked.

If possible, bury any remaining ashes or offerings in the earth, or keep a pinch of ash as a talisman of transformation.

Whether a small candle or a bonfire, a Lughnasadh fire carries something of the old rhythm. Lighting it marks the turning of the season, a time to give thanks for what’s been gathered and to let go of what’s no longer needed. Every harvest, in some way, asks for both.

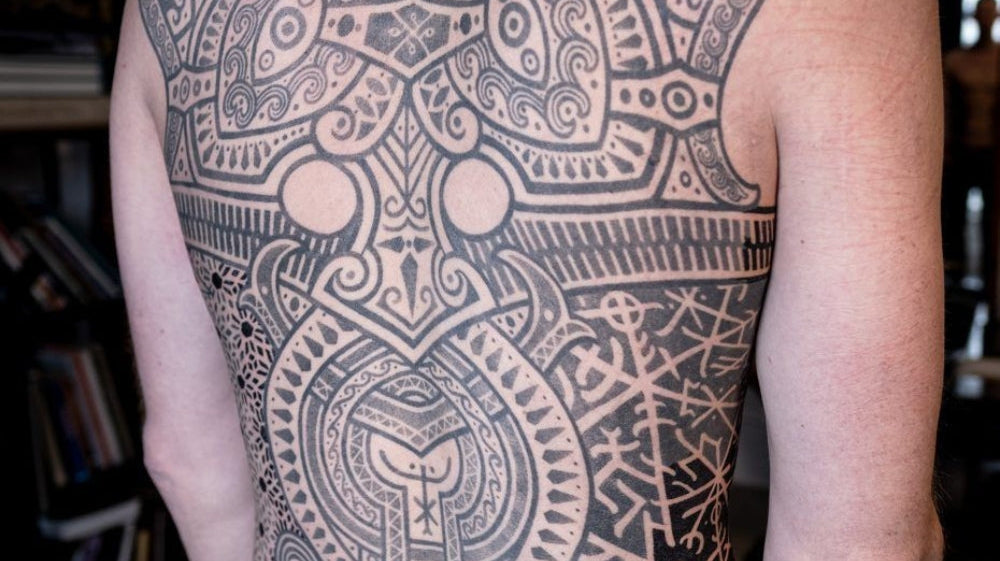

LUGHNASADH AND TATTOO SYMBOLISM

Lughnasadh is more than a seasonal marker; it’s a moment of reflection, a reminder that what we plant in times of light will eventually come to harvest, for better or worse. For some, that process is marked not just in ritual, but on the skin. Tattoos can serve as lasting symbols of intention, change, or personal devotion — a way to carry the meaning of the harvest within, long after the season has passed.

And who better to guide that expression than Lugh, the god of light, skill, and many talents?

Lugh is the ultimate polymath. He’s a god of craftsmanship, poetry, war, strategy, music, and healing — master of all arts, and slayer of the tyrant Balor with a spear of light.

You might feel drawn to Lugh if you are:

-

A creative professional or artisan — for example, a writer, blacksmith, tattooist, musician, builder, coder, healer.

-

A jack-of-all-trades who finds strength in versatility.

-

Someone seeking to reclaim confidence, skill, or a new creative identity.

-

On a personal journey of self-mastery, integration, or renewal after struggle.

- A child of the sun or the fire that remains when the sun begins to fade.

NEED SOME INSPIRATION? THE NORDIC TATTOO TRIO BOOK BUNDLE CONTAINS ANCIENT ARTISTIC EXPRESSIONS SPANNING NORDIC, CELTIC, PICTISH, AND BEYOND

STILL STANDING AT THE CROSSROADS WITH A LOAF AND A LIGHTER?

Lughnasadh isn’t about perfection. It’s about taking stock of what’s grown, what’s gone, and what still matters. Whether you mark the season with a fire, a loaf, a tattoo, or a long walk through tall grass, the point is simply this: show up. Offer something back. Honour the work.

AND IF YOU WANT TO CARRY THE HARVEST A LITTLE FURTHER — ON YOUR SKIN, YOUR SHELVES, OR YOUR ALTAR — YOU’LL FIND SOMETHING TO LOVE IN OUR SHOP.

Author: Isar Oakmund, Tattooist, Norse symbolism enthusiast & co-founder of Northern Black