How did the festive Christmas as we know it today shape itself over time? It did not arrive fully formed, nor was it carefully planned; rather, it developed gradually from a patchwork of older seasonal customs observed across Europe long before Christianity spread north. Much of what we now recognise as Christmas has its roots in pagan holiday traditions, which is why the question “Is Christmas a pagan holiday?” refuses to go away.

So yes, it all started with people we call pagans, who did not call themselves pagans!

WHO WERE THESE PAGANS?

Once Christianity started spreading throughout Europe around the 4th century, the missionaries encountered people, cultures, and groups that believed in different and older systems, religions, and traditions. Everyone who was not Christian was seen as pagan to these missionaries. It originated and remained an offensive term for a long time; only in recent decades has it begun to be reclaimed by modern practising pagans. It is an umbrella term for many cultures, religions, and beliefs. But it essentially meant “non-Christian”.

Different sources claim that some of these Christians were fascinated by pagan ways, so they incorporated those traditions into Christianity; others argue that pagan traditions and sites were simply adopted by Christianity, as it was a practical way to convert non-believers.

Early Church sources indicate that missionaries were often encouraged to work with existing pagan customs rather than try to wipe them out, especially when those customs were tied to long-established festivals or sacred places. In a letter to Augustine of Canterbury, Pope Gregory I argued that familiar practices should be adapted for Christian use, on the practical grounds that people were more likely to accept change when it did not require abandoning everything at once.

Wodan Heals Balder’s Wounded Horse, Emil Doepler, 1905

But let’s start with the date of Christmas itself. Why December 25th, in the middle of winter? December 25th does not appear in Christian sources until the 4th century, first recorded in the Roman Chronography of 354, which is surprisingly late for such a firmly insisted-upon date. Earlier Christians were generally uninterested in birthdays, viewing them as pagan practices, which makes the later certainty about Jesus’s birth date quietly ironic.

However, there’s a list of pagan celebrations that specifically honour the god (or gods) of the sun, so there is a good chance Christians took inspiration from that. These celebrations were held around the winter solstice and were called Yule in Western Europe, Yalda in Iran, and Inti Raymi in Peru. But the one that is perhaps the closest to our modern version of Christmas is the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia.

SO, WE KNOW THAT CHRISTIANS TOOK AND ADAPTED PAGAN TRADITIONS, BUT WHICH ONES SPECIFICALLY?

Saturnalia was an Ancient Roman holiday celebrated between the 17th and 24th of December, honouring the god Saturn. He was the god of agriculture and around that time of the year, the last planting season would be completed. During this festive time, the ancient Romans would observe a week of celebrations.

Traditionally, this time would be filled with gambling, socialising, playing music, and singing. Alongside these, gift-giving was one of the primary traditions as the Romans believed those small acts of kindness would bring a bountiful harvest in the following year. There would be feasts to go around and widespread cheerfulness, much like the festive celebrations we have today.

Fir branches and other greenery would be brought into homes to brighten this dark and gloomy time of the year, which is possibly where the idea of having a Christmas tree in our houses originated.

Evergreen plants weren’t originally festive decorations so much as practical signs that life went on. When most of the landscape looked dead or dormant, fir branches stayed green, and that brought great hope. When Christianity later took up the practice, it didn’t need much explaining, mainly because people already understood what those branches were meant to signify.

ODIN ENDURED NINE NIGHTS ON YGGDRASIL TO GAIN WISDOM. HANGING HIM ON YOUR TREE REQUIRES CONSIDERABLY LESS SACRIFICE.

Saturnalia was also famous for temporarily turning Roman society upside-down, allowing slaves to dine with their masters, mock them openly, enjoy public celebrations, wear free citizens’ clothing, and not work on the last day of the festival.

In some households, a mock “King of Saturnalia” was appointed whose role was to issue deliberately absurd commands, reinforcing that normal order was officially suspended.

In the Saturnalia festival, the 25th of December was considered the climax and had a special name – Brumalia (also known as Sigillaria by some sources). On this day, many Romans would give their loved ones small terracotta figurines, which is believed to be an evolved tradition that previously involved human sacrifice.

So, as the bible does not actually give Jesus’s birthday, arguably the most important thing we have taken from Saturnalia is the date. Given that there are even theologians who concluded that Jesus was probably born sometime during spring, which would explain the shepherds and sheep in the Nativity story.

AND WE COME TO THE VIKINGS AND THEIR TRADITIONS…

Yule is considered one of the oldest pagan celebrations happening during the Winter Solstice.

To start off easy, the word “Yule” comes from a Viking festival that was held to keep optimistic spirits high during the cold and dark days of winter. Yule is a festival observed during the winter season that was practised by the Germanic and Scandinavian people, and later incorporated into the Christmas holiday as missionaries converted pagans to Christianity.

For many, this overlap is why the idea of a “pagan Christmas” exists at all. Yule was not replaced so much as rebranded, with many pagan Yule traditions carrying on under Christian names. Even today, guides on how to celebrate Yule often focus on the same core ideas: light in darkness, shared food, remembrance, and marking the turning of the year.

Like Saturnalia, Yule is also a sun-themed celebration. In Old Norse, Jul (Jol) could refer to a feast to the sun or even one of Odin’s nicknames, the Yul-father, due to his strong association with the sun. Of course, a widespread tradition like this will have many differences in the specifics based on location. Some regions might celebrate for 12 days or a month, but they mostly start on the Winter Solstice. It is important to note that the Winter Solstice typically falls on the 21st or 22nd of December, but historically, it was celebrated on the 25th of December.

Pre-Christian Germanic calendars weren’t especially tidy, so festivals like Yule didn’t always land on the same date each year. It was probably understood less as one specific night and more as a stretch of midwinter, which made it easier, later on, to pin it to a fixed date once Christian calendars took over. That’s why arguments about whether Christmas borrowed its timing from Saturnalia or Yule tend to be a bit speculative.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PAGAN WHEEL OF THE YEAR THROUGH CELTIC AND NORDIC TRADITIONS

TOAST-RAISING, GIFT-GIVING, HOSPITALITY-DEMANDING AND EVIL SPIRIT-WARDING

The tradition of raising ceremonial toasts during Christmas gatherings has roots in Yule drinking rituals, where toasts were made to gods, ancestors, and future prosperity.

In the Viking Age, these were often structured rounds, each with symbolic intent. Today, the symbolism is lighter, but the ritual remains — even if it now honours “the year ahead” rather than Odin.

While already mentioned decoratively, evergreens also had a protective function in Norse belief. Bringing greenery indoors was thought to ward off malevolent spirits during the long winter nights, when the boundary between worlds was believed to be thinner.

The lights came later. The instinct to keep winter darkness politely outside did not.

Modern carolling has echoes of midwinter procession traditions, where groups moved between homes singing, drinking, and sometimes demanding hospitality. These were not always polite affairs. In Scandinavia and parts of northern Europe, refusal to participate in such customs was believed to bring misfortune. Today’s carolers are considerably less threatening, though still capable of causing mild discomfort.

In Viking societies, gift-giving reinforced bonds, loyalty, and obligation, rather than simple generosity. Gifts created relationships that carried expectations. Modern Christmas gifts are framed as freely given, but the underlying social pressure — and memory of who gave what last year — suggests the older logic has not entirely disappeared.

Children hauling a Yule log, Britannica

The tradition involving a Yule Log is a widespread tradition with many localised differences, even though its origin is not fully known. The Yule log likely started out as a practical way of keeping a fire going through the darkest part of winter, particularly in Germanic and Scandinavian households where letting the hearth go cold could be a real problem. A large log would be brought in at midwinter and left to burn slowly, sometimes over several days, and in some places for all of yuletide.

Fire at that point in the year wasn’t just useful, it was reassuring. As long as the hearth stayed lit, things were more or less holding together. That’s what turned the simple act of choosing, carrying in, and lighting the log into something ritualistic, even if no specific god was being called on.

It is also a tradition that has undergone massive changes due to the times, particularly in how people live in mass-populated cities, often without space for it, or for safety reasons. The decline of large hearths and open fires in urban homes made the physical Yule log impractical. By the 19th century, especially in France, the tradition transformed into the bûche de Noël — a log-shaped cake that preserved the symbolism without the fire risk.

GIVE THE GIFT OF FORESIGHT THIS YULE WITH OUR RUNE READER BUNDLE:

MISTLETOE BEFORE KISSING

Another part of our Christmas tradition that has roots in the Viking Age is the mistletoe. And it all stems from a Norse myth that goes like this. Baldr, son of Odin and Frigg, was driven to insanity and paranoia, plagued by visions of his own death. Frigg made every earthly object vow to never harm Baldr. He became known for his untouchable nature. All was good until Loki made a weapon out of mistletoe, the one thing that had not taken Frigg’s vow. Baldr was murdered, and once Frigg started crying, her tears graced the branches of mistletoe and turned into the white, pearl-like berries that now forever lie as a symbol of her love for him.

In some pre-Christian traditions, mistletoe symbolised fertility, peace treaties, and liminality — a plant that belonged neither fully to earth nor sky.

Mistletoe is a hemiparasitic plant, meaning it grows attached to the branches of trees rather than rooting itself in soil. To pre-modern observers, this made it an anomaly: it wasn’t planted, it didn’t sprout from the earth, and yet it clearly lived. It didn’t fall from the heavens like rain or snow, and it wasn’t celestial like the sun, moon, and stars either. It simply appeared on the branches of trees, suspended between the two realms, arriving without an obvious beginning. Existing in this liminal space, it was associated with fertility, protection, and oath-making rather than romance, as things that did not belong fully to one realm were believed to hold particular power.

Its association with romantic kissing is a much later Victorian development and would have meant very little to the Vikings themselves. I can’t imagine they’d have considered needing to be stood under a specific plant to steal a kiss.

The History of the Mistletoe, Details Flowers

FOOD, PRESERVATION, AND SURVIVING WINTER

Many foods we now think of as “traditional Christmas fare” have less to do with celebration and more to do with getting through winter. Midwinter was when fresh food was hard to come by, so feasts were built around whatever would keep: salted or smoked meats, dried fruits, nuts, root vegetables, and strong drinks that wouldn’t spoil.

Spices, which we now associate with luxury and festivity, were originally used to preserve food, mask the taste of ingredients that had seen better days, and make the same winter meals feel a little less repetitive. Heavy cakes, dense breads, and fruit-filled puddings weren’t designed to be light or elegant — they were meant to last, provide energy, and be eaten slowly over the long stretch of winter rather than finished in one sitting.

Drink mattered too. Ale, mead, and later mulled wine were often safer than standing water and much easier to store through the colder months. In Norse and Germanic societies, drinking at Yule wasn’t just about excess; it marked hospitality, continuity, and shared survival, with toasts raised not only to gods, but to ancestors and the year still to come.

Even the scale of the feast mattered. Slaughtering livestock at midwinter reduced the burden of feeding animals through the cold months while ensuring communities had enough preserved meat to last until spring. What we now recognise as indulgence was, in many cases, careful seasonal planning.

Modern Christmas food retains this structure almost intact. It is heavy, rich, spiced, preserved, and excessive by design — a reminder of a time when getting through winter was not guaranteed, and eating well at midwinter was both reassurance and quiet defiance.

ODIN SLEIGHS

And our last one before we go, we have to talk about Odin. The Allfather was the father of all the gods and has been traditionally portrayed as an old man with a long white beard, accompanied by his eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, whom he would ride among the skies, much like Santa is depicted in modern portrayals with his reindeer. Kids during winter would fill their boots with carrots and place them around the chimney in hopes of Odin coming by and leaving presents in return for Sleipnir eating those carrots. Remind you of something?

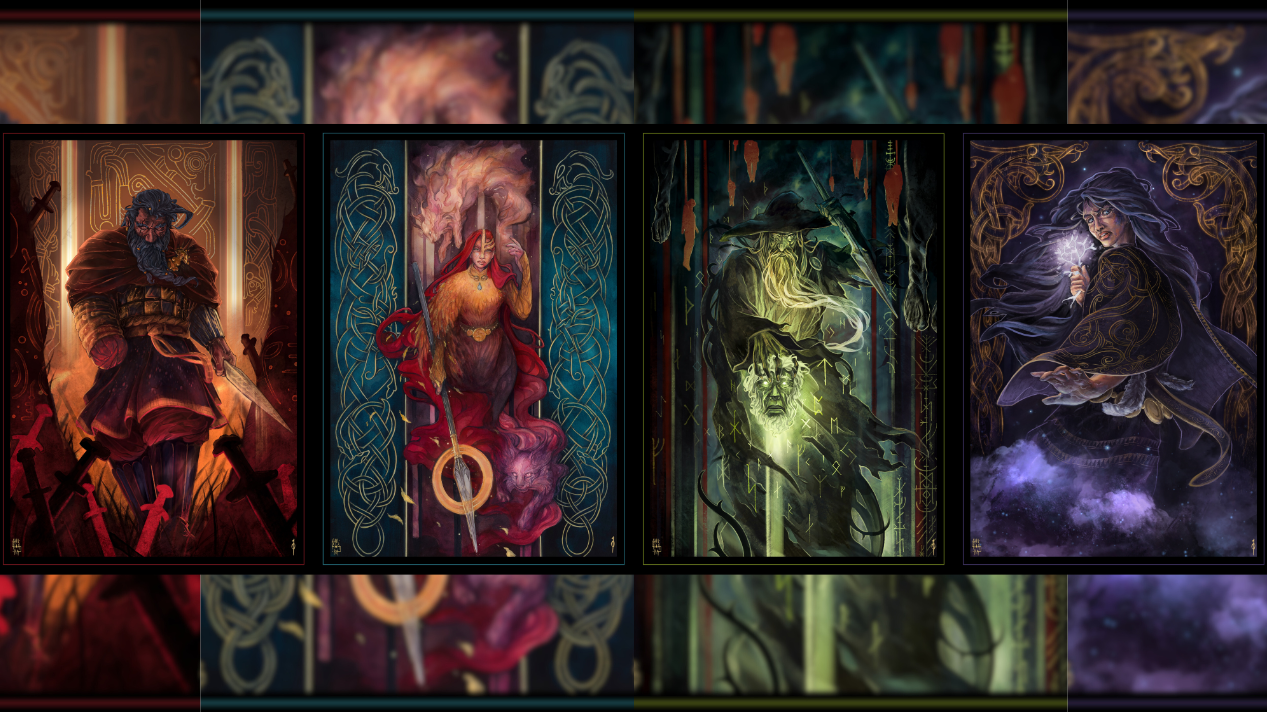

WHAT WOULD PAGAN SANTA LOOK LIKE? WE THINK HE’D SLEIGH:

YULE BLESSINGS

We will leave the blog at that. We hope you’ve learned something interesting and enjoyed uncovering a few lesser-known threads behind the season. However you choose to mark the dark months — with old traditions, new ones, or something in between — we wish you a steady hearth, good company, and Yule blessings.

IF YOU LIKE CONTENT LIKE THIS, MAKE SURE TO SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER, WHICH OFTEN HAS FREE DESIGNS AND INTERESTING HISTORY LESSONS.

First published: 12 December 2024

Updated: 6 January 2026