The wheel turns, the shadows lengthen, and we reach the ancient threshold between light and dark. For many paths, this is Samhain — the festival that closes the bright half of the year and opens the dark. In the Celtic Wheel of the Year, Samhain marks both ending and beginning: a time for fire, remembrance, and standing at the thin place between worlds.

Across the northern lands, another rite once echoed this same turning — the Norse Álfablót, a quiet autumn sacrifice held in honour of the elves and the dead. Where Samhain became the communal Pagan Halloween, Álfablót was its private counterpart: a household ritual for ancestors and hidden spirits at the start of winter.

In this article, we’ll explore Samhain’s meaning, ancient and modern Samhain rituals, and how Viking and Norse traditions like Álfablót reveal shared roots of remembrance, harvest, and reverence for the unseen.

WHEN IS SAMHAIN?

Samhain (pronounced “SAH-win” or “SOW-win”) is classically observed from sunset on October 31st to sunset on November 1st, in the Gaelic tradition.

In many modern Pagan practices, it is stretched or observed over the Samhain eve as the more magical moment. Because the Celts counted days from dusk to dusk, the "eve" is integral to the observance.

As one of the cross-quarter days, Samhain sits roughly halfway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice — it is both an ending and a beginning, a time when the old year is laid to rest and the dark half is born.

For many modern Pagans, Samhain becomes a season, not just a single night — a time to slow, to lean into remembrance and quiet.

THE MEANING OF SAMHAIN — LIMINALITY, DEATH, AND REBIRTH

THE END OF SUMMER, THE START OF WINTER

Etymologically, Samhain is sometimes rendered as “summer’s end,” though scholars debate the precise roots.

Regardless of its linguistic origin, in practice the festival marks the shift of seasons: the final harvest is gathered, fields are laid fallow, livestock are culled or housed, and nature’s vitality recedes.

In Celtic society, the waning daylight, colder nights, and the visible decay of plant life carried real weight. To the Celts, the sun’s strength was receding — they understood Samhain as a moment when the powers of darkness grew stronger.

In some chronicles, the Celts saw Samhain as the turning of the year’s end — in effect their “New Year’s Eve” in ritual gravity.

VEIL-THINNING AND COMMUNION WITH THE DEAD

One of the central features of Samhain’s meaning in Pagan consciousness is the notion that the boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead (or the Otherworld) is at its most porous.

It is said that spirits of the departed can wander among us, and the gods may choose to venture into the mortal realm. Because of that, Samhain is a time for remembrance, offerings, ancestor veneration, insight from the unseen, and sometimes even negotiation with spirits.

In this way, Samhain also functions as a death-and-rebirth threshold: death is not only the end but also the passage. In the silence of winter, all things gestate; Samhain is the doorway through which seeds of transformation cross.

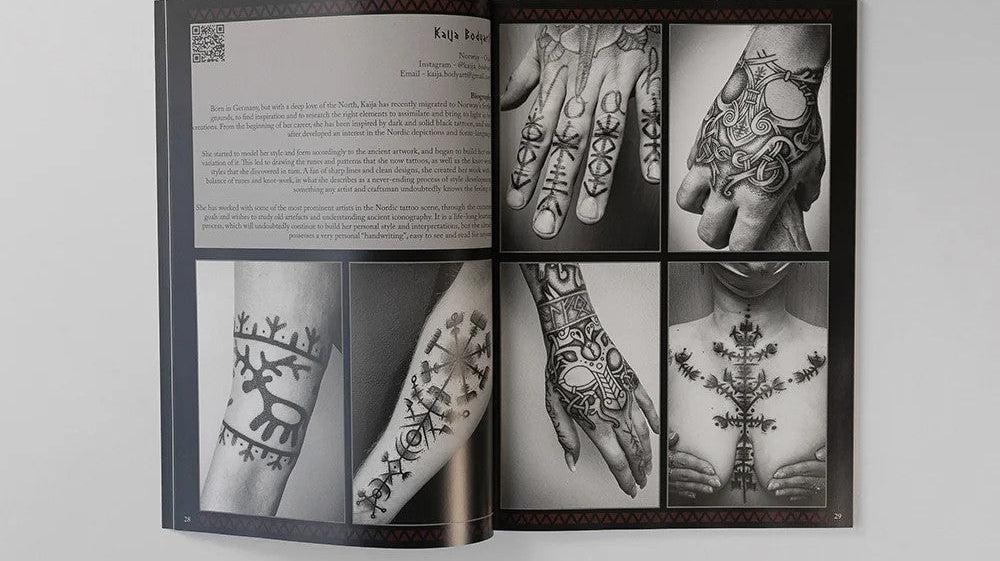

FOR YOUR SAMHAIN ALTAR: A SKULL ENGRAVED WITH BIND RUNES SYMBOLISING LOSS, DEATH, MEMORY AND GRIEF:

CELTIC & PAGAN TRADITIONS: SAMHAIN RITUALS AND PRACTICES

Over centuries, Samhain rituals and traditions evolved. Many we know today are modern reconstructions or survivals, but they draw on older patterns.

FIRE, BONFIRES, AND HEARTH RENEWAL

In early Irish tradition, Samhain saw what is called the Great Fire Festival — communal bonfires lit as a sacred blaze. Older hearths would extinguish and be kindled anew from the common fire, symbolising unity, protection, and renewal.

In some accounts, only the great fires could burn; private hearths were forbidden to kindle new flame until relit from the communal blaze.

In addition, the winter fires were thought to assist the sun in its weakening course — fire as a solar proxy or petition.

OFFERINGS FOR THE DEAD AND THE FAIR FOLK

At Samhain, households would set a place for ancestors at the ancestral table, leaving food, drink, and tokens. Plates might be left outside for spirits or the “wee folk”— faeries, pookas, sidhe beings.

In Gaelic customs, guisers (costumed wanderers) would go from house to house, offering entertainment or recitation in exchange for food or offerings, perhaps as a form of giving to the dead or placating wandering spirits.

DIVINATION, PROPHECY, AND UNVEILING

Divination was deeply woven into Samhain tradition. Because the veil between realms was thin, many oracular practices were reserved for this night. Some would read apple peels, nuts, or the shapes of shadows in the fire; others might consult ogham staves, runes, or the casting of bones.

In some medieval accounts, stones or tokens representing people would be placed around a fire, and if one were “lost” or missing in the morning, it signified danger or death for that person in the coming year.

Bobbing for apples — sometimes called dooking or snapping for apples — began as a Samhain divination ritual, not a party game. Apples were sacred in Celtic tradition, linked with immortality, prophecy, and the Otherworld. At Samhain, unmarried people would try to bite an apple floating in water or hanging from a string; success was said to foretell the next year’s marriage or fortune.

MASKS, DISGUISES, AND BOUNDARY-WALKING

Because spirits might roam among the living, many Samhain traditions emphasised disguise — masks, costumes, or anonymity — to confuse malevolent beings or prevent harm.

Over time, this practice evolved into “trick-or-treat”-style customs, as households left out food and strangers (or children) came in disguise to request offerings or blessings.

Turnip lanterns (later pumpkins) were carved and lit to ward off spirits — the ancestor of the jack-o’-lantern.

WEAR YOUR OWN FREYA GODMASK THIS SAMHAIN:

SILENCE, STILLNESS, AND THE DUMB SUPPER

Another practice is the Dumb Supper — a silent meal taken in darkness or candlelight, with an empty chair or place set for the departed — the quiet and stillness open space for communion, memory, and listening.

Other contemporary elements are walking the land in darkness, gathering fallen leaves, listening to wind and shadow, or meditating at graves or standing stones.

STEP-BY-STEP SAMHAIN RITUAL

Below is a ritual outline rooted in Celtic and modern Pagan practice. Adapt to your tradition, local laws, safety, and spirit.

Timing: At dusk/as night falls on October 31st

Duration: 45–75 minutes (or more)

Setting: Outdoors preferred (if safe), or in a quiet indoor corner

What you’ll need:

-

Altar cloths in dark/twilight tones

-

One or two black, deep red, or purple candles

-

A small dish or bowl for offerings

-

Tokens: Rune stones (or ogham stones, or inscribed bones), herbs, seeds, leaves, apples or nuts

-

A journal or paper + pen

-

Fireproof dish (if burning paper)

-

Optional: Shell bowl of water, salt, incense and a bell.

1. PREPARATION & INVITATION

Clean and clear your space. Silence smartphones. Meditate briefly: breathe in, breathe out, centre your mind. Before beginning the ritual, set a simple boundary of protection — this could be visualising a circle of protective white light or calling in your guardian spirits to witness and protect. Speak your intention aloud:

“On this night of thinning veil, I invite memory, guidance, and protection. May our ancestors and kind spirits walk here in peace.”

2. KINDLING THE SACRED FIRE/LIGHTING A CANDLE

If doing a fire (outdoors): light a central blaze. If indoors: light your candles. Use words like:

“By flame and shadow I call the unseen. Let the door stand open tonight, let the ancestors pass.”

3. HONOURING ANCESTORS AND THE DEAD

Call on your ancestors, whether by name or by silence. Place a token or a leaf in the offering bowl for each. Speak:

“To you who walked before, may your memory live. Thank you for your counsel, your blood, your light.”

Leave a portion of food or drink (bread, cider, water, nuts) as an offering.

4. PROPHETIC OR DIVINATORY WORKING

Invoke a question or theme you wish guidance on. Draw a rune, ogham, or cast bones. Reflect on what the symbols tell you. Write or speak your insights.

If working with apple peels or nut shells, observe their shape, alignment, or patterns in the fire.

5. RELEASE AND TRANSFORMATION

On slips of paper, write what you wish to release (fear, grief, harmful habit) and what you choose to carry forward (strength, promise, wisdom).

Burn (safely) or bury the “release” slip; place beneath the candle, or keep the “carry” slip as a lodestone.

6. COMMUNION AND SILENCE

Sit or stand in silence for a few minutes, breathing and listening. Invite any messages, images, or whispers from the stillness.

7. CLOSING AND THANKS

Thank the ancestors, gods, spirits, and elements you have named. Extinguish candles with intention:

“Gate is watched, door is closed, but memory endures.”

If outdoors, return ashes or natural offerings to the earth or water with respect, and take away anything not of the land — wax, metal, or ribbon — to dispose of mindfully elsewhere.

8. SHARE OR REFLECT

Break bread or share a quiet feast. Record insights in a journal. Let the night seep in and listen to what stirs beneath the dark.

LEARN HOW TO MAKE MEMORIAL BIND RUNES WITH OUR BOOK:

THE THREADS OF TRADITION: SAMHAIN LEGACY TODAY

Pagan Halloween is in many ways Samhain reimagined: costumes, lanterns, trick-or-treating, ghost stories, and feasts. But unlike purely secular Halloween, our focus in a Pagan context is on deep thresholds, remembrance, and transformation.

Modern Pagans often:

-

Create ancestor altars

-

Perform a silent or small-group ritual

-

Leave offerings outside

-

Use divination as spiritual guidance

-

Walk at dusk or in the woods

-

Honour the night as sacred.

Because Samhain is a turning point, it asks: What dies, what persists? What seeds gestate in dark soil? Through ritual, we give language to transition, to grief, to hope.

RELATED: BEGINNERS GUIDE TO NORSE RUNES, SIGILS & BIND RUNES

DID THE VIKINGS CELEBRATE HALLOWEEN OR SAMHAIN?

The Vikings did not celebrate Samhain, yet they marked the darkening of the year in their own way. As autumn deepened and the harvest ended, each household turned inward for Álfablót — the sacrifice to the elves. It was one of the most private and secretive rites in the old calendar, held not in temples or great halls but at home, among family.

ÁLFABLÓT: THE HIDDEN FEAST OF THE ELVES

The word blót means “sacrifice” or “offering,” where blood is spilt, and álfar — often translated as “elves” — are not the type you’ll find at the North Pole. In Heathen belief, they were powerful, often ancestral spirits connected to the land, the mound, and the family’s luck (hamingja). Some were the souls of honoured dead, others were local guardian powers tied to the farm. To honour them was to maintain right order between the living and the unseen.

A QUIET RITE BEHIND CLOSED DOORS

Unlike the great seasonal blóts to the gods — open feasts of ale, sacrifice, and oath — Álfablót was a private affair. Each household held its own, closing the doors to outsiders. Even fellow countrymen were turned away when the elves were being honoured.

The best account we have comes not from a priest or chronicler, but from a poet — Sigvatr Þórðarson, the Norwegian skald who served King Ólafr Haraldsson. Around 1018 CE, Sigvatr travelled east through Sweden on royal business, carrying King Haraldsson’s word to the Swedish court — a Christian messenger in lands where the old rites still held strong. He recorded his journey in a poem called Austrfararvísur (“Verses of an Eastern Journey”).

In his verses, Sigvatr tells of arriving at a farmhouse one autumn evening, seeking shelter. The door was shut against him. The people inside refused him entry, saying that a blót was being held and that “no Christian may come in.” At the next farm, he found the same. Finally, at a third homestead, the woman of the house called out that they were “honouring the elves” and that he must keep away. Sigvatr takes the rejection with dry humour — his verses make light of it, but they also record the quiet authority of those who still kept the old ways.

This was Álfablót — not a public celebration, but a household sacrifice. Each family kept its own relationship with the elves and the ancestors. Outsiders, even respected travellers, were forbidden to witness it. Within the farm walls, offerings of food, ale, or blood were made to the unseen kin who guarded the land and its luck.

The secrecy was part of its sanctity. The household became a small, sealed world for one night: a boundary between the living and the dead, the seen and the unseen. Once the rite was complete, life resumed, but that silence and reverence would have lingered like the smell of the autumn hearth.

DRINK TO YOUR ANCESTORS WITH OUR MUGS OF KINGS:

TIMING AND SEASON

Álfablót seems to have fallen after the harvest, likely in late October or early November — the same turning of the year marked by Samhain in Celtic lands. Some scholars place it near the Dísablót, another autumn rite honouring the dísir (female ancestor-spirits), and suggest the two may once have overlapped or shared purpose. Both acknowledge the same truth: the bond between the living and the dead grows thin as the light fails.

WHAT WAS OFFERED AT ÁLFABLÓT

Archaeology and comparative study offer clues. The Old Norse sources use blót broadly to describe animal sacrifice and food or drink offerings. For Álfablót, it was likely food, ale, and blood, shared with the elves through the earth itself. Meat and ale from the household’s own stores were offered at the hearth, by the mound, or near boundary stones. Some believe a portion of the winter’s first brew was poured out for them.

It was an act of reciprocity: a share for those who came before, in return for their continued protection and fertility of the land. If the elves were pleased, the farm prospered; if neglected, misfortune might follow.

THE ELVES THEMSELVES

The earliest mentions of the álfar come from the Eddas, where they appear as an integral part of the cosmic order.

In Grímnismál, the god Odin names Álfheimr, “the world of the elves,” as one of the divine realms, gifted to the god Freyr when he was a child. In Völuspá, elves are said to have been shaped soon after the dawn of creation, their origins bound to those of humankind and the dwarves.

Snorri Sturluson later divided them into two kinds — ljósálfar (light-elves) and dökkálfar (dark-elves) — describing the first as fairer than sunlight and the second as blacker than pitch. Most scholars now read this as symbolic rather than literal: an expression of the elves’ dual nature as bringers of life and death, fertility and decay.

ELVES AND THE DEAD

In later Scandinavian tradition, burial mounds are called álfhóll — “elf-mounds.” This continuity is not accidental. The álfar were long believed to dwell within the earth, in the same places where the honoured dead were laid to rest. Many scholars, from Folke Ström to Hilda Ellis Davidson, interpret the álfar as the souls of ancestors who had become powers of the land.

To feed the elves, then, was to feed one’s own dead. In this sense, Álfablót was not a festival for strangers or wandering spirits — it was a communion with one’s lineage.

NATURE AND CHARACTER

The álfar were neither wholly kind nor cruel. They were reciprocal beings: their goodwill had to be maintained through respect.

Neglect them, and sickness, infertility, or ill-luck might follow. Please them, and the household thrived. They were not gods to be worshipped, but kin to be kept on good terms with.

It is no surprise that Álfablót was private. The living did not display their communion with the dead; they tended it quietly, as one tends the fire at night.

WOMEN AND THE HOUSEHOLD CULT

Evidence suggests that women likely led the Álfablót. The rite was domestic, centred on hearth and lineage — both under female care in Norse society. Women oversaw the family’s spiritual balance: they kept the fire, guarded the keys, and maintained the household’s hamingja. It would have been their duty to speak to the mound and ensure the unseen kin were honoured.

In this, Álfablót mirrors Samhain’s ancestral focus. Both festivals draw the living into conversation with the dead; both depend on respect, food, and remembrance.

ECHOES OF ÁLFABLÓT TODAY

Modern Heathens and Pagans who honour Álfablót often do so simply: a candle at the hearth, a cup of ale poured outside, a few words to the ancestors. Privacy is key — the act belongs to the household, not the wider community. In this, the old custom survives: quiet, personal, and unbroken.

Álfablót reminds us that the heart of Norse spirituality was not always the feast or the battlefield, but the home. Its purpose was to keep peace between the living and the unseen, to recognise the shared fate of all who draw breath, and to carry gratitude into the dark half of the year.

CHANNEL THE SPIRIT OF VIKING AGE SORCERY WITH OUR ÁLFABLÓT T-SHIRT:

SAMHAIN AND ÁLFABLÓT — THE SHARED THRESHOLD

Samhain and Álfablót stand on opposite sides of the old world, yet they speak the same language. Both mark the deep turn of the year, when the fields are bare and the breath of winter gathers at the door. Both belong to the quiet hour between harvest and frost — when the living draw inward, and the unseen draw close.

It’s a small wonder that both Samhain and Álfablót honour the dead, yet name them differently — the fae in the Celtic lands, the elves in the North. Different tongues, same instinct: to feed and remember the unseen ones who walk between worlds. One was public, one private; both were acts of remembrance and renewal.

Each teaches that death is not an ending, but a return. The year falls away, yet life continues beneath it — in seed, soil, and memory. The veil between worlds is not a wall but a seam, and through it passes breath, story, and blessing.

So whether you keep Samhain by firelight or pour ale to the roots in the old way, the work is the same: to honour what has passed, to tend the bond that endures, and to carry gratitude into the dark half of the year.

May the ancestors walk beside you.

May your offerings be well received.

And may the door between worlds stand open — just wide enough for wisdom to pass through.

HONOUR YOUR ANCESTORS WITH PIECES THAT KEEP THE OLD STORIES CLOSE — EXPLORE OUR BOOKS, ART, AND CLOTHING INSPIRED BY NORSE AND CELTIC TRADITION