Across pre-Christian Northern and Western Europe, the changing seasons were marked with shared rites, not only for harvest or survival but also for reverence and a good relationship with the land. These festivals rose from a way of life where nature, ancestry, and spirituality were all part of the same breath.

In modern Paganism, many of these seasonal moments are gathered into the Wheel of the Year — a framework of eight sabbats that echoes older Celtic fire festivals, Norse blóts, Druidic solar rites, and even Christianised feast days. While not identical across cultures, the themes of light and dark, life and decay, sowing and reaping remain remarkably consistent.

This guide offers a grounded look at each point on the wheel as it appears through the lens of Celtic, Norse, and folk European traditions. Whether you are walking the wheel as part of your spiritual path or simply seeking to understand the older currents beneath modern holidays, you are entering a cycle that honours both the land and those who walked it before us.

WHAT ARE THE EIGHT PAGAN SABBATS?

The eight Pagan Sabbats reflect seasonal changes and the eternal cycle of birth, growth, death, and renewal.

Each sabbat aligns with a key point in the solar and agricultural calendar, celebrated by pre-Christian cultures across Northern and Western Europe. Modern Pagan paths, particularly Wicca, often divide these eight festivals into two groups: the Greater Sabbats and the Lesser Sabbats.

GREATER SABBATS (CROSS-QUARTER DAYS / FIRE FESTIVALS)

The four festivals of the Greater Sabbats fall between the solstices and equinoxes. They are often called fire festivals because they traditionally involved sacred bonfires, rituals of purification, and seasonal transitions that were vital for both survival and spiritual continuity. They are more rooted in Celtic tradition, and often marked major turning points in agricultural and community life.

-

Samhain – End of the harvest, ancestor veneration

-

Imbolc – First stirrings of spring, sacred to Brigid

-

Beltane – Fertility, fire, and sacred union

- Lughnasadh / Lammas – First harvest, grain and sacrifice

These are considered the Greater Sabbats because of their historical depth and the intensity of communal ritual often involved.

LESSER SABBATS (QUARTER DAYS / SOLAR FESTIVALS)

The Lesser Sabbats fall on the solstices and equinoxes; when the sun reaches its peak or stands in perfect balance. These days were sacred to many cultures, marking the shift between light and dark, warmth and cold, sowing and harvest. Across Europe, they were often tied to local myths, planting cycles, and the rhythms of everyday life.

-

Yule (Winter Solstice) – Rebirth of the sun, longest night

-

Ostara (Spring Equinox) – Balance, renewal, fertility

- Litha (Summer Solstice) – Power, abundance, peak sunlight

- Mabon (Autumn Equinox) – Harvest, balance, thanksgiving

Though called “Lesser” Sabbats, they are no less important. They mark the solar heartbeat of the year, often linked with mythic battles, sacred unions, or the rise and fall of nature’s powers.

WHY IS IT CALLED A SABBAT?

The word “Sabbat” has an unusual history. It comes from the Hebrew Shabbat, meaning “rest,” and is commonly known to us in modern times as the sabbath. It took on a different meaning in medieval Europe. Back then, it was used by the Church to describe so-called witch gatherings, which they imagined as nocturnal, orgiastic, heretical rites. This image arose during the witch hunts and Inquisitions of the Middle Ages.

In the 20th century, early Wiccans and modern Pagans reclaimed the word to describe seasonal festivals celebrating nature, the sun, and the land. The term “sabbat” came to refer to each of the eight holy days on the Wheel of the Year, blending ancient European folk traditions with contemporary spiritual practice.

So, while the word's journey includes religious misunderstanding and persecution, its modern use by Pagans is an act of revival and redefinition — it honours sacred time, seasonal change, and connection to the old ways.

Let’s look at each sabbat in a bit more detail.

SAMHAIN — 31ST OCTOBER TO 1ST NOVEMBER

KNOWN AS:

- Old Irish: Samain or Samfuin

- Modern Irish: Samhain

- Scottish Gaelic: Samhainn or Samhuinn

- Welsh: Calan Gaeaf ( "First Day of Winter")

- Norse: Winternights (Vetrnætr)

- Wiccan: Samhain

- Druidic: Samhuinn

- Christian: All Hallows’ Eve, All Saints’ Day

- Mexican (parallel): Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead)

Theme: Death, remembrance, and the thinning veil.

Time of Year: End of harvest, start of the dark half of the year.

In the Celtic lands, Samhain marked the turning of the year; when the final harvest was brought in, animals were culled, and the boundaries between the living and the dead were believed to grow thin. Making it the perfect time for divination, ancestral rites, and protective workings. Fires were lit on hilltops to cleanse and safeguard communities. Offerings were left out to appease wandering spirits and ancestral kin.

In Old Norse tradition, the corresponding festival is Vetrnætr, or Winternights — a three-day observance held at the onset of winter. Little is recorded about the rituals practised, but surviving lore and sagas suggest it was a time to honour the dísir (female ancestral spirits) and the landvættir (spirits of the land). It was also associated with the goddess Freyja, who was connected to fertility and the dead.

Though the customs differ from place to place, the heart of this season is shared. It’s a time to turn inward, honour the dead, and prepare ourselves for the long dark ahead. As the nights grow longer, many still look to their ancestors, not in fear but for steadiness, remembrance, and the kind of strength that carries us through.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Today, many Pagans mark this time by setting up ancestor altars, lighting candles in memory of the dead, or holding silent “dumb suppers” where a place is set at the dinner table for the departed. Divination is commonly practised, particularly with runes or tarot cards, and seasonal bonfires are still lit. The folk customs now absorbed into Halloween, such as costume-wearing, pumpkin carving, and trick-or-treating, can trace their roots back to earlier protective and appeasement rites designed to navigate a night when spirits walked freely.

YULE — WINTER SOLSTICE (~21ST DECEMBER)

KNOWN AS:

- Norse: Jól (Yule)

- Druidic/Celtic Revival: Alban Arthan ("Light of Arthur") – a Welsh Druidic term

- Modern Irish poetic references: Grianstad an Gheimhridh ("Winter Solstice")

- Wiccan: Yule

- Roman: Saturnalia

- Christian: Christmas.

Theme: Rebirth, endurance, the returning light.

Time of Year: Midwinter, the longest night of the year.

At the heart of Yule lies the Winter Solstice — the moment when the longest night gives way to the returning light. For those who lived closely with the land and sky, it carried deep spiritual meaning. It marked the sun’s return and was a sign that life always finds a way, no matter how harsh the winter.

In Celtic and Druidic traditions, Yule was a time for fireside storytelling. The tale of the Oak King and the Holly King locked in their seasonal struggle, told of the eternal cycle of growth, decay, and renewal. Fires were kindled, and evergreens — symbols of life enduring through winter — were brought indoors to honour the continuity of life.

Among the Old Norse, Jól (Yule) was one of the most sacred times of the year. The season spanned several days and was marked by blóts (offerings), oath-swearing, feasting, and the veneration of ancestors and deities. During this time, it was said that Odin, in his winter guise, led the Wild Hunt across the sky — a ghostly procession of spirits and gods. Families would leave out offerings to guard their homes and invite good fortune. The Jóltree, decorated with sun symbols, fruit, and protective charms, has clear roots in what we now know as the Christmas tree.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Today, many folks follow Yuletide traditions by lighting Yule logs or candles, decorating with evergreens, and sharing meals in warmth and gratitude. In many ways, it survives through Christmas customs: the decorated tree, gift-giving, carols, wreaths, and feasts all echo earlier rites of renewal and ancestral honouring.

For modern Pagans, Yule is also a time to reflect inwardly, honour household spirits and departed kin, and mark the victory of light over darkness, not just in the sky but within the soul.

READ MORE: YULE ENJOY LEARNING ABOUT PAGAN ORIGINS OF CHRISTMAS TRADITIONS!

IMBOLC — 1ST TO 2ND FEBRUARY

KNOWN AS:

-

Old Irish: Imbolc or Oímelc (“ewe’s milk”)

-

Modern Irish: Imbolc

-

Scottish Gaelic: Là Fhèill Brìghde ("Feast Day of Brigid")

-

Welsh: No direct analogue, but Gwyl Ffraid (Feast of Brigid) is used by modern practitioners.

- Druidic: Festival of Light

-

Wiccan: Imbolc

-

Christian: Candlemas

- Norse: Dísablót (occurs late Jan/early Feb).

Theme: Awakening, feminine power, spiritual renewal.

Time of Year: First signs of spring; lambing season.

Imbolc marks a quiet shift — the first signs that winter is loosening its grip. In the Celtic tradition, it’s a festival of light and fresh beginnings, held in honour of Brigid, goddess of the hearth, healing, and poetry. Lambs are born, snowdrops break through frozen soil, and something small but certain begins to stir in the land and in ourselves.

At this time of year, the hearth was central, with homes ritually cleansed and Brigid’s crosses woven from straw and hung above doorways for protection and blessing. Wells and springs were honoured as sources of healing. Fires were lit not just for warmth but to invite insight, purification, and renewal.

In Christian Ireland, Brigid lived on as Saint Brigid of Kildare — one of the country's patron saints — her day is still marked on 1st February.

In the Norse world, the festival of Dísablót occurred around this same period. Though distinct in form, it shares the seasonal theme of feminine spiritual presence. The dísir — female ancestral spirits and divine protectresses — were honoured in private or communal rites. Their blessings were sought for fertility, protection, and guidance as the people prepared for the season ahead. It was a time to recognise the unseen guardians who watch over families and land.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Today, Imbolc is marked by lighting candles in windows, setting intentions for the coming season, and honouring the divine feminine in its many forms. Many Pagans still craft Brigid’s crosses, bless hearths and homes, or leave symbolic offerings at natural springs.

Candlemas, marked on 2nd February in the Christian calendar, still holds something of Imbolc in its bones, especially in its focus on light, cleansing, and the blessing of candles. Both speak to a quiet turning point in the year, a sense that winter is softening and something new is beginning to stir.

OSTARA — SPRING EQUINOX (~21st March)

KNOWN AS:

- Anglo-Saxon: Ēostre

- Druidic Revival (Welsh): Alban Eilir ("Light of the Earth")

- Modern Irish: Grianstad an Earraigh ("Spring Solstice/Equinox") — not traditional but used in neo-pagan contexts

- Wiccan: Ostara

- Christian: Easter (named after Ēostre)

- Persian (parallel): Nowruz.

Theme: Balance, fertility, renewal.

Time of Year: Spring Equinox, day and night in perfect balance.

At the Spring Equinox, the year pauses in perfect equilibrium. Light and dark are momentarily equal, and life begins its vibrant return to the land. In the Anglo-Saxon tradition, this time was sacred to Ēostre, a goddess associated with dawn, fertility, and the renewing forces of spring. Her symbols, hares, eggs, and blooming flowers, mirror the fertility of the field and forest.

Though Ostara, as a named festival, is relatively new, its motifs are ancient. The Druidic observance of Alban Eilir (“Light of the Earth”) likewise celebrates this threshold of growth, light, and awakening. Rituals at this time often honour balance in the self and in nature, an inner preparation to match the external blossoming.

No recorded blót is specific to the equinox in the Norse world, yet the season’s spirit would have been observed in practice. Offerings to Freyr, Freya, or other Vanir deities — patrons of fertility, prosperity, and peace — would have been fitting. Agricultural rhythms and the stirring of the earth held profound importance in Norse cosmology, even if unmarked by a formalised rite.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Today, many Pagans mark Ostara by planting seeds, laying spring flowers on their altars, or greeting the sunrise in honour of the returning light. Traditions like painting eggs and tales of the Easter Bunny live on in the Christian calendar, but their roots stretch back to older fertility customs and symbols of new life.

BELTANE — 1ST MAY

KNOWN AS:

- Old Irish: Beltaine or Beltine

- Modern Irish: Bealtaine

- Scottish Gaelic: Bealltainn

- Welsh: Calan Mai ("First Day of May")

- Norse/Germanic: Walpurgisnacht (30th April)

- Druidic: Alban Bealtaine

- Wiccan: Beltane

- Modern: May Day

- Roman (parallel): Floralia.

Theme: Fertility, vitality, sacred union.

Time of Year: Height of spring; rising life force in land and body.

Beltane is the fire festival of fertility and flourishing, celebrating life’s wild, creative energy as spring bursts into full bloom. In the Celtic regions, hilltop bonfires were lit to bless the land and herds. Couples would leap over flames to receive fertility blessings, and cattle were driven between twin fires to protect them from illness in the months ahead. The festival honoured reproduction and the sacred union between land and sky, goddess and god, spirit and matter.

The Druidic festival of Alban Bealtaine likewise marked the awakening of the green world, the turning point when growth became unstoppable. It was a liminal time when the veil between worlds was thin, not for the dead, but for nature spirits and fae, whose goodwill could be courted or earned through offerings and reverence.

In Germanic and Norse cultures, the evening of 30th April, known as Walpurgisnacht, was steeped in magic and transformation. Fires blazed on hilltops across Scandinavia and central Europe, lit to ward off bad luck and wandering spirits. Folks said witches and wights moved through the dark that night, but so did the earth’s waking energy. Though not a formal blót, the night echoed many of Beltane’s themes: protection, fertility, and the joy of a season turning.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Today, Maypole dancing, leaping over fire, and flower crown-making remain popular ways to mark this festival of passion and possibility. Many modern Pagans offer milk, honey, or flowers to household spirits or the land itself, reviving earlier customs of seasonal reciprocity. Wiccans may mark the sacred union of the divine masculine and feminine, while others use the day to celebrate life force, sexuality, creativity, or simply the joy of existence in a fertile, waking world.

LITHA — SUMMER SOLSTICE (~21ST JUNE)

KNOWN AS:

- Celtic: Litha

- Druidic Revival (Welsh): Alban Hefin ("Light of the Shore" or "Light of Summer")

- Modern Irish: Grianstad an tSamhraidh ("Summer Solstice")

- Norse: Midsommar

- Druidic: Alban Hefin

- Wiccan: Litha

- Slavic (parallel): Kupala Night

- Christian: St John’s Day.

Theme: Abundance, illumination, divine union.

Time of Year: Summer Solstice; sun at its zenith

Litha, the height of light, marks the longest day and shortest night of the year. It is the turning point when the sun, though still strong, begins its slow descent — a moment of both abundance and impermanence. This balance was mythologised through the battle between the Oak King (ruler of the waxing year) and the Holly King (who reigns from Midsummer to Midwinter) in the Celtic and Druidic traditions. Fires were lit to honour the sun and ensure the health of crops and kin through the remainder of the growing season.

In Norse and Germanic cultures, Midsommar was a celebration of fertility and light and a sacred time of connection to the land and its spirits. Villages gathered to raise maypoles, weave flower crowns, and engage in communal rites near rivers, lakes, or sacred groves. Fire and water, representing purification and vitality, were central. Magic was believed to be especially potent, and certain herbs gathered at Midsummer, like St. John's Wort, were said to carry heightened power.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Many Pagans mark Litha by lighting fires at dusk, gathering herbs said to carry the sun’s strength, and celebrating while watching the sunset. Some still craft sun wheels — rolled down hillsides or set alight — to honour the turning year. It's a time for giving thanks, seeking clarity, and standing in one's own light.

Midsommar is still joyfully celebrated in Scandinavia, with flower crowns, dancing, and long tables set under an open sky. The maypole is raised, songs are sung, and the land is honoured for all it gives at the height of summer.

LUGHNASADH — 1ST AUGUST

KNOWN AS:

- Celtic: Lughnasadh (Festival of Lugh)

- Old Irish: Lugnasad ("Assembly of Lugh")

- Modern Irish: Lúnasa

- Scottish Gaelic: Lùnastal

- Welsh: Gwyl Awst ("Feast of August")

- Anglo-Saxon: Lammas (“Loaf Mass”)

- Norse: Freyrblót (linked to harvest and fertility)

- Wiccan: Lughnasadh (some traditions use Lammas)

- Modern: First Fruits Festival.

Theme: Gratitude, sacrifice, the first harvest.

Time of Year: Beginning of harvest season; grain cutting.

Lughnasadh, held at the start of August, marks the first of the Celtic year’s three harvests. It’s a time of gathering, gratitude, and remembrance — a reminder that every abundance comes with effort and sometimes sacrifice. The god Lugh is said to have founded the festival in memory of his foster mother Tailtiu, who died after clearing the land for crops. In her honour, communities came together with games, feasting, and rites of thanks as the first grains were brought in.

In Anglo-Saxon England, this same festival became known as Lammas, or “loaf-mass,” when the first bread baked from the new wheat was brought to church and blessed. The symbolism of grain cut down in its prime to feed others spoke deeply to agricultural people living close to the land.

Among the Norse, though no single harvest festival is recorded in the surviving sources, scholars and practitioners associate this season with Freyrblót, a rite to honour Freyr, the Vanir god of fertility, peace, and prosperity. Closely tied to the land and its fruitfulness, Freyr was a natural figure to thank as the first crops came in and the year began to turn toward winter.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Many Pagans mark Lughnasadh or Lammas by baking bread, crafting corn dollies, or offering the first fruits of their garden. It’s a time to give thanks but also to reckon with the cost of growth, and what must be let go for something greater to thrive.

In some Christian churches, Lammas loaves are still brought forward for blessing — a lingering trace of older harvest rites. Whatever name you give this festival, Lughnasadh, Lammas, or Freyrblót, it’s a time to stop and take stock. To honour what the land provides and ask honestly: what are we giving back?

MABON — AUTUMN EQUINOX (~21ST SEPTEMBER)

KNOWN AS:

-

Welsh Modern Pagan: Gŵyl Mabon

- Druidic Revival (Welsh): Alban Elfed ("Light of the Water" or "Light of Autumn")

-

Modern Wicca: Mabon (named in the 1970s after the Welsh god Mabon ap Modron)

-

Christian: Michaelmas (29th September)

- British Folk: Harvest Festival.

Theme: Balance, gratitude, preparation.

Time of Year: Autumn Equinox, equal light and dark before the descent into winter.

The autumn equinox stands at a moment of stillness, when day and night are again equal and the final fruits of the harvest are gathered. Though the festival name “Mabon” is a modern Wicca addition, its spirit of thankfulness and reflection draws from deep ancestral soil. In Alban Elfed, the Druidic observance, light and dark are honoured as sacred twins — one giving way to the other in the eternal rhythm of the wheel.

Traditionally, people offered apples, grain, nuts, and wine to the gods, ancestors, and spirits of the land. It was a way of showing respect for the earth’s abundance and asking for favour for the lean months ahead.

Though there is no direct Norse blót aligned with the autumn equinox in surviving lore, the shift in the season would still have been felt and honoured. Communities likely made offerings to the landvættir, shared harvest meals, and began readying themselves for the long winter ahead. It was a time for gratitude, storing what could be kept and turning thoughtfully toward the darker half of the year.

MODERN OBSERVANCE:

Many Pagans today mark Mabon by bringing the season indoors — with autumn leaves, apples, grain, and other harvest fruits. Some share meals, others light candles or make offerings in quiet thanks. It’s a time for reflection: taking stock of what’s been gathered, letting go of what’s run its course, and finding balance before the darker months ahead.

The Christian feast of Michaelmas and British harvest festivals clearly borrow from older traditions, with shared meals, harvest hymns, and community food offerings.

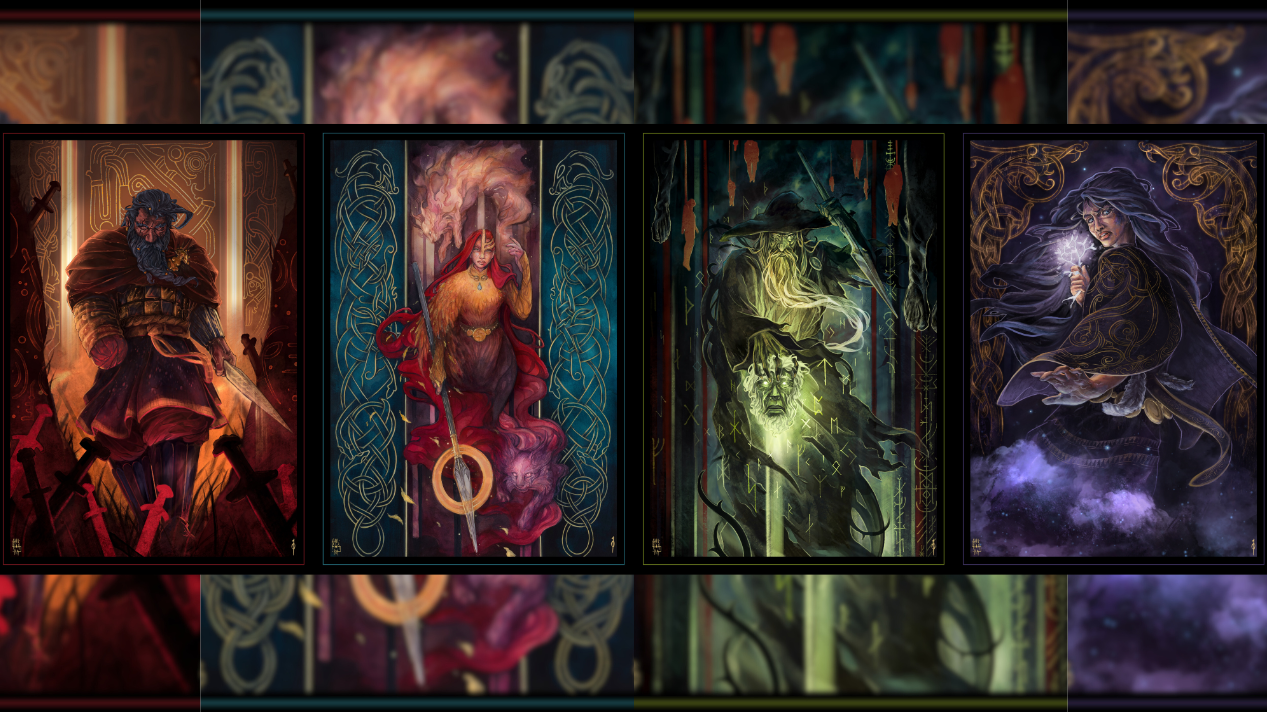

LOOKING FOR INSPIRATIONAL INK? CHECK OUT OUR NORSE AND VIKING TATTOO BOOKS

BEYOND THE WHEEL: NORSE PAGAN HOLIDAYS OUTSIDE THE EIGHT SABBATS

The Wheel of the Year, as commonly celebrated in modern Paganism, is a rich framework for marking solar and seasonal shifts. However, it is a synthesis, a weaving of Celtic, Wiccan, Druidic, and folk European traditions. For Norse Pagans and those following Heathen or Ásatrú paths, the original seasonal observances followed their own rhythms.

Some Norse festivals loosely overlap with the eight Sabbats, but many stand apart. These blóts weren’t part of a fixed calendar — they followed the land’s needs and the people’s rhythms. Rooted in local traditions, they honoured the landvættir (spirits of the land), the dísir (female ancestors), and the gods of the Æsir and Vanir. Each rite was a giving and an asking — an offering made in the hope of strength, protection, or a good harvest in return.

RELATED: WHAT ARE NORDIC RUNES? MEANING AND HISTORY

What follows are the sacred festivals of the Norse year, accompanied by their resonant runes, symbols that echo the spirit of each rite.

ÁLFABLÓT — EARLY TO MID-NOVEMBER

A quiet, solemn rite of the household, Álfablót was a deeply personal offering to the álfar, the elemental spirits often associated with the land and burial mounds. The word álfar is often translated as “elves,” but not the kind found in storybooks or Christmas tales. In Norse belief, they were something older and deeper — ancestral nature spirits. Not playful or harmless, but formidable, potentially dangerous, and worthy of veneration and offerings.

Álfablót was not a public celebration, but a private communion with the unseen, held at the hearth or grave. Outsiders were turned away; the home became a temple, offering a bridge between bloodlines.

Theme: Ancestral veneration, connection to nature spirits, protection during the dark season.

Associated rune: ᛉ Algiz (Elk)

-

Guardian of the soul-road, protector of sacred space.

- This rune wards the threshold, opening paths between worlds while shielding those who walk them.

DÍSABLÓT — LATE JANUARY OR EARLY FEBRUARY

This sacred rite honoured the dísir, fierce female spirits, possibly goddesses or ancestral mothers. Often led by women, Dísablót sought protection, fertility, and foresight for the coming year. Though it roughly aligns with Imbolc, its cultural flavour is distinctly Norse.

Theme: Feminine power, guardianship, and spiritual foresight.

Associated rune: ᛃ Jera (Year/Harvest Cycle)

-

Signifies cyclical time, fertility, and natural rhythm.

- Jera reminds us that blessings unfold in their own time and that ancestors walk within our every season.

SIGRBLÓT — MID-TO-LATE APRIL

As the snow loosened its grip and the land breathed again, warriors and farmers gathered for Sigrblót, the Blót of Victory. Offerings were made to Odin, Týr, and Freyr, asking for success in battle and farming. Offerings were made for courage, good fortune, and the resolve to meet what was coming with honour and clear intent.

Theme: Victory, masculine energy, agricultural and martial success.

Associated rune: ᛏ Tiwaz (Tyr)

-

Sword-point of justice, the rune of rightful striving.

- Ideal for warrior rituals, oath-taking, or blessings for courage.

VÁRBLÓT — SPRING’S DAWN (DATE VARIES)

Less widely known but no less sacred, Várblót honoured the Vanir gods of fertility, peace, and union. Possibly held at the turning of spring, this blót may have included blessings of fields, marriages, and the hidden seed beneath the soil. Where Sigrblót calls forth strength, Várblót invokes gentle fruitfulness and sacred relationship.

Theme: Fertility, growth, divine union.

Associated rune: ᛜ Ingwaz (Fertility)

-

Symbol of seed energy, sacred union, and earthly abundance.

- Closely linked to Freyr, making it perfect for planting rites.

MIDSOMMAR (SUMMER SOLSTICE) — LATE JUNE

Though part of the wheel as Litha, the Norse Midsommar has its own folk roots. Celebrations included flower crowns, fertility rites, and divination rituals. Fire and water played central roles in both spiritual and practical ways.

Theme: Vitality, illumination, joy, and connection to the natural world.

Associated runes: ᛋ Sowilo (Sun) or ᛇ Eiwaz (Yew)

-

Sowilo represents the sun’s strength, clarity, and divine will

- Eiwaz is the Yew of transformation, a gateway between worlds.

FREYRBLÓT — EARLY AUGUST

With the first fruits cut and stored, Freyrblót was a rite of gratitude to Freyr, the Vanir god of peace, fertility, and sacred kingship. Fields were blessed for continued yield, and the people gave thanks for food and the spirit of harmony that allows life to flourish.

Theme: Harvest, prosperity, balance with the land.

Associated rune: ᛃ Jera

- Jera again calls here the eternal return, the ripening of good effort.

- Freyr is the green flame of life, and Jera is its measure.

VETRNÆTR (WINTERNIGHTS) — LATE OCTOBER

Occurring at the start of winter, this festival involved offerings to the landvættir and the dead. It often marked the transition from public to indoor rites and kicked off the spiritual “wild season” that culminated at Yule.

Theme: Ancestors, resilience, preparing for the long night.

Associated rune: ᚾ Nauthiz (Need)

-

Rune of survival, hardship, and inner fire

- Reflects the necessity of endurance, sacrifice, and community.

BROWSE OUR ALTAR PIECES TO HONOUR THE GODS, SPIRITS AND TURNING OF THE WHEEL

RUNES AND RITUAL: WEAVING THE OLD THREADS INTO MODERN PRACTICE

These Norse festivals don’t sit neatly on the modern Pagan calendar; they sing their own song, shaped by the land, the gods, and our ancestors.

Working with runes alongside these traditions brings another layer of meaning. A well-chosen rune can sharpen your focus, honour old ways, or strengthen your intent. Whether you’re offering to Freyr in spring, holding quiet space for the álfar, or warding hearth and threshold, the runes stand as companions — part sign, part spell, part memory.

CHECK OUT OUR RUNE BOOKS, RUNE STONES & RUNE READINGS

WALKING THE PAGAN WHEEL OF THE YEAR

The Pagan Wheel of the Year is a pattern older than memory, shaped by light and dark, hunger and harvest, firelight and frost. It tells us what our ancestors always knew: that the seasons turn, that each has its work, and that we belong to that turning.

From Samhain’s silence to Midsummer’s joy, from hearth-blessings in winter to bread-breaking in the first days of August, our path is well-worn. The names shift — Lughnasadh becomes Lammas, Yule becomes Jól — but the heart of it remains the same: to honour, give thanks, and begin again.

To walk the wheel today is not to re-enact the past but to reawaken it. To find your place between earth and sky, roots and stars.

HONOUR THE SEASONS WITH SYMBOLS THAT LAST — EXPLORE OUR HANDCRAFTED RUNES, ALTAR PIECES & NORSE JEWELLERY.

Author: Isar Oakmund, Tattooist, Norse symbolism enthusiast & co-founder of Northern Black