In the Viking Age, jewellery was never just jewellery. A brooch, bead, or arm ring carried meaning. It could bind a man to his lord, show the wealth of a household, or act as a charm against whatever the world might bring. Norse jewellery crossed seas, changed hands in trade, was buried with the dead, and hung from the necks of the living as both treasure and talisman.

Archaeological discoveries, from the grand Oseberg ship burial in Norway to hoards scattered across Britain and Scandinavia, reveal stunningly beautiful and deeply symbolic jewellery. These objects were living artefacts of belief, protection, and prestige to the Vikings.

MAGIC, PROTECTION, AND SPIRITUAL SIGNIFICANCE IN VIKING JEWELLERY

For the Vikings, a pendant, brooch or ring could shield against harm, be used as a prayer to the gods or a vessel for unseen power. When you wore these items, you were wearing magic on your body. Here are some of the common spiritual motifs found in Viking jewellery designs.

THOR’S HAMMER (MJÖLNIR)

Of all Viking amulets, none is found more than Thor’s hammer (Mjölnir). Small silver and bronze hammers have been unearthed in Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, and the British Isles, as well as in Slavic territories. You would likely see them hanging around the necks of Viking-age farmers, traders and warriors. To wear a Mjölnir necklace was to carry Thor’s strength.

It was also quite a rebellion. As Christianity crept north, Thor’s Hammer became the badge of loyalty to the old gods.

Most of the hammers found were located in the graves of women, who have not been identified as warriors in these instances. Sadly, we have no knowledge of why this is, but it is very likely that it was such a common symbol of protection that the more martial prowess of Thor was ignored, in order to protect the home.

SUN AND COSMIC MOTIFS

The sun symbolises life, growth and renewal, and it too found its way into Viking jewellery. Sun wheels, spirals, and swastika-like patterns, known as Fylfot, (long before that symbol was twisted in the 20th century) appear again and again. These shapes echoed the cycles of day and night, season and harvest. When you wore them, you wore the turning of the heavens, the eternal rhythm of the world.

THE TRIQUETRA

The Triqueta — three interlaced arcs — shows up on Viking rune stones and coins, and sometimes on jewellery. Today, many call it a “trinity knot”, but the design is far older than Christianity. It was used widely across Europe in Celtic, Germanic, and other pagan art as far back as the late Iron Age. Its meaning isn’t pinned down, but the power of three runs through Norse mythology: the three Norns weaving fate, the three roots of Yggdrasil, the three functions of the gods. The knot could be read as life, death, and rebirth, or simply as eternity — an unbroken line without beginning or end (wyrd).

KNOTWORK

Knotwork was everywhere in Viking art. Beasts with bodies twisted into endless ribbons were carved into brooches and arm rings. Some scholars think this interlacing was about more than style; it was used as a protective charm — a way of binding chaos so it could never reach the wearer. Whether or not that’s true, its sheer intricacy speaks to a belief that order and beauty had power of their own.

If you want to wear something in this tradition, have a look at our Njord Godmask Necklace, worked in the Mammen style — a divine face framed in knotwork.

RUNES FOR POWER AND PROTECTION

Then there are the runes. They weren’t just marks to spell a name; they were thought to carry force in themselves. The Hávamál tells us how Odin won them: by hanging from Yggdrasil for nine nights, pierced by his own spear, until the runes revealed themselves. From then on, they were his gift to humanity: symbols to carve for protection, prophecy and blessing. Their significance is recorded in Old Norse texts such as the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, our primary sources for Viking myth and cosmology.

RUNES ON JEWELLERY AND AMULETS

Archaeological finds confirm this belief in the runes’ potency. Viking Age graves and treasure hoards have yielded jewellery, amulets, and bracteates (thin gold discs) inscribed with runes. These inscriptions are often short — sometimes just a single symbol — but they could carry powerful meaning: A name, an invocation, a blessing. Even one letter could change an object into something more than itself. When you scratched a rune into silver, you gave it a voice.

ANIMAL MOTIFS

If runes spoke in symbols, animals roared in imagery. Viking jewellery is alive with creatures — wolves, serpents, boars, ravens — each chosen not at random but for their mythic and magical weight. As Viking warriors carved beasts into ships and weapons to draw on the creatures’ power and skill, it seems likely their forms were added to jewellery for the same purpose.

-

Ravens: Linked to Odin’s messengers Huginn and Muninn, ravens symbolised wisdom, foresight, and the watchful eye of the gods. Pendants and brooches depicting ravens may have been worn to invoke Odin’s guidance, or simply to remind others that wisdom and foresight stood at the wearer’s side.

-

Wolves: Feared and revered in equal measure, wolves evoked ferocity, loyalty, and kinship. Wolf-head arm rings from Gotland suggest they were used for strength and protection. Were they always just wolves? Perhaps. But in Viking belief, the wolf could wear many faces — the faithful Geri and Freki at Odin’s side, or Fenrir, the monstrous wolf fated to devour him at Ragnarök. The jewellery leaves us guessing: some motifs may simply show the strength of the animal itself, while others could hint at these mythic beasts.

-

Serpents and dragons: Twisting beasts coil through Viking art, encircling brooches, rings, and pendants. Sometimes they are simple serpents, sometimes dragons, sometimes the Midgard Serpent itself — Jörmungandr, who holds the world in his coils and will one day rise against Thor. Were these designs meant to bind chaos, to ward off destruction, or to invoke the sheer scale of cosmic power? Perhaps all three.

-

Boars: The boar was sacred to Freyr and Freyja, gods of fertility, luck, and abundance. Golden-bristled boars like Gullinbursti appear in myth as gifts from the dwarves. A boar pendant on the chest could have been a prayer for prosperity, or a charm to bring courage in war and fruitfulness at home.

-

Bears and horses: Less common, but potent when they appear. Bears carried the ferocity of the berserkers, warriors who were said to fight in the bear’s frenzy, shielded by its spirit. They were seen as vigilant protectors, often linked with sacred spaces, most famously appearing in the Oseberg mound.

Horses, meanwhile, were tied to travel between worlds — none more so than Sleipnir, Odin’s eight-legged steed. A horse etched on jewellery may have marked a wish for safe journeys, or a link to the paths between life and death. Indeed, many sacrificed horses have been found in Viking burials, presumably to carry their master to the halls of the gods, and also as a statement of power and rank. Horses were immensely valuable, so only the elite could afford such a sacrifice.

These animal images were far more than ornaments — they were amulets of power, spirit guides worn so their strength might live in the wearer.

If you’d like a piece in this style, our Midgard Serpent Bronze Ring coils twice around the finger, echoing the eternal embrace of the world serpent.

JEWELLERY AS CURRENCY: WEALTH AND TRADE IN VIKING SOCIETY

Vikings were expert traders, and their jewellery was frequently exchanged in trade, particularly across their vast networks extending into the Byzantine Empire, the Middle East, and beyond. There were no silver mines in Scandinavia, so every fragment had to be won by trade, raid or tribute. That made jewellery your bank account, your status and your oath.

WEIGHT SYSTEMS

The Vikings traded by weight, not coin value. A scale and set of weights were found in many traders' graves, often alongside silver jewellery. A decorated arm ring could be both a public badge of loyalty and a reserve of cash. If you needed to buy, you clipped a piece off and weighed it. Jewellery was a way to carry your wealth into the hall, the market and even the grave.

HACK-SILVER AND ARM RINGS

By National Museums Scotland - National Museums Scotland, CC BY-SA 4.0

Archaeologists have found large amounts of hack-silver — chopped-up pieces of silver jewellery (rings, chains, brooches, ingots) — in Viking hoards across Scandinavia, the British Isles, and beyond. These weren’t broken accidentally; they were deliberately cut to be weighed for trade. Silver arm rings, in particular, were often hacked into segments to pay for goods.

At sites like Cuerdale Hoard (England), Galloway Hoard (Scotland), and finds from Gotland (Sweden), we see both complete jewellery and hacked pieces, showing jewellery’s dual role as status display and currency reserve.

If you want to wear that history, our Hedeby Coin Silver Earrings echo the first Scandinavian coinage — a nod to jewellery’s role as both treasure and tender.

BEADS: PORTABLE WEALTH AND COSMIC COLOUR

If silver spoke of loyalty and oath, beads spoke of travel and wonder. They are found most often in women’s graves, strung between the fabulous oval tortoise brooches that fastened their dresses. Each bead was a bright fragment from the wider world.

-

Amber from the Baltic, golden and protective.

-

Glass from Frankish and Byzantine workshops, glowing in colours that seemed almost magical.

-

Carnelian and garnet from the Islamic Caliphate and as far as India, carried along trade routes that stretched beyond imagination.

But beads may also have carried magic. Amber was prized for its warmth and supposed power to ward off evil. Some scholars think the sequence of colours in a beaded necklace may have hidden meanings: a protective charm or ritual order. We cannot be sure, but it fits the Viking way of thinking that everything could carry power if its intention were set correctly.

Our Silver Gotland Crystal Pendant carries that same spirit — a clear, glinting treasure, named for the great trade hub of Gotland, where beads and silver poured in from every corner of the known world.

JEWELLERY AS A SIGN OF STATUS AND IDENTITY

Viking jewellery was also a marker of social status.

VIKING ARM RINGS

When a chieftain clasped an arm ring around his warrior's bicep, it was more than payment. It was an oath. That silver band meant loyalty, protection and the promise to stand together in war. If the bond was ever broken, the arm ring could be snapped in two, a public shattering of trust.

WOMEN’S VIKING BROOCHES AND BEADS

Women's jewellery spoke just as loudly, though in different ways. The famous oval “tortoise” brooches that fastened a woman’s dresses declared not only her standing, but that of her entire household: bronze for the everyday farmstead; silver or gilded brooches for the families of wealth and influence.

Between those brooches hung strings of beads — bright stones and coloured glass from around the world. To see a woman wearing amber from the Baltic, glass from Byzantium, or Carnelian from the Caliphate was to see her household’s reach, its connections, and its prosperity. Her jewellery was her family’s résumé, displayed right at the heart of her attire.

JEWELLERY IN DEATH

When death came, you didn’t leave your identity behind; you carried it into the grave. Across Viking-age Scandinavia, women of rank were often buried with intricately crafted brooches, strings of imported beads, and finely made pins.

In central Norway, excavations at places like Valsøyfjord have uncovered burial chambers containing hundreds of miniature beads alongside ornate brooches — clear signs of both status and cultural connections. These mesmerising objects still speak across the centuries, reminding us what their communities already knew: that these women had been powerful, well-connected, and sacred in their roles.

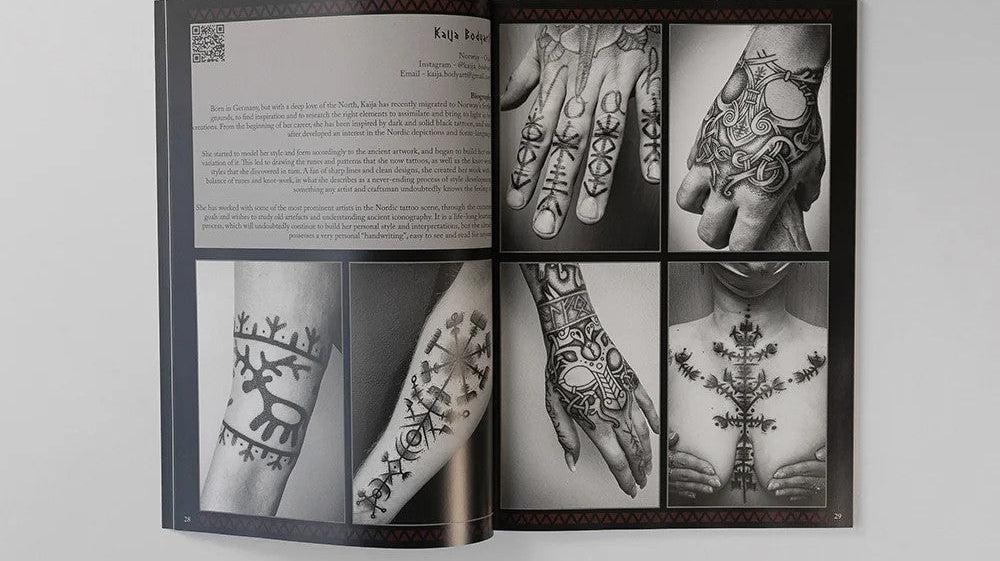

STYLES OF JEWELLERY AND ART ACROSS THE VIKING AGE

The art of the Vikings shifted, flowed, and grew more intricate as centuries passed. Each style tells us something about the age it came from, its beliefs, and the worlds the Vikings moved through. Jewellery carried these styles in miniature, worn on the body as markers of faith, wealth, and fashion.

OSEBERG STYLE (800–900 CE)

Kulturhistorisk Museum/University of Oslo

The Oseberg burial, unearthed in Norway in 1904, gave its name to the earliest of the great Viking art styles. Flowing, ribbon-like animals twist and knot into near-abstract forms, serpents and birds caught mid-motion. On brooches and pendants, the designs seem alive — a spirit world tangled into silver and bronze. These early works carry the raw energy of pagan belief, when animals and gods were never far from the human world.

BORRE STYLE (850–950 CE)

From the burial mounds at Borre in Norway came the next flourish of design. Here, the art grows denser, more knotted, full of gripping beasts and looping interlace. Round brooches from this period show creatures with staring eyes and gripping paws, locked into endless knots. This was jewellery as a protective snare, binding chaos in curves of silver.

JELLINGE STYLE (950–1050 CE)

Named for the royal site of Jelling in Denmark, this style marks a world in transition. Pagan animal forms remain — serpents, lions, horses — but now Christian crosses and motifs begin to creep in. The figures are more open, their lines clearer, as if the old gods and the new faith were meeting on the same brooch. Jewellery from this age whispers of compromise and change, as Scandinavia shifted towards Christianity.

MAMMEN STYLE (970–1025 CE)

The burial at Mammen in Denmark revealed designs that were both bold and refined. Here, animals twine with foliage, knotwork blossoms into tendrils and leaves. It is Viking art tempered by Christian influence — worldly, elegant, and favoured by kings and their retinues. A brooch in the Mammen style wasn’t only wealth; it was a statement that its wearer stood at the heart of power, where politics and faith entwined as tightly as the patterns themselves.

RINGERIKE STYLE (1050–1150 AD)

A Viking Age runic inscription from the early 11th century, in a limestone coffin in Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. The creature on the stone may represent Sleipnir, Odin's eight-legged horse. Image by David Beard, MA - St Paul's Church (London), Public Domain

By the turn of the millennium, the style called Ringerike had emerged. Named after stone carvings in Norway, its animals are leaner and more naturalistic, often lions and birds with flowing manes and wings. The jewellery of this time carries the stamp of European influence — the Vikings were no longer just raiders, but rulers and traders integrated with the wider medieval world. Silver brooches and rings from this period gleam with Norse pride and continental grace.

URNES STYLE (1050–1150 AD)

The last great style of the Viking Age — named after the stave church at Urnes — was all about elegance and fluidity. It featured slender beasts twisting in long, ribbon-like lines, looping into almost calligraphic shapes. Christian crosses appeared alongside serpents and lions as old beliefs began to fade, but never fully vanished. Jewellery in the Urnes style feels virtually timeless, bridging pagan and Christian, Viking and medieval, myth and history.

Learn more about Viking art styles in our collection of Viking, Pagan & Nordic Artwork Books.

CARRYING THE VIKING JEWELLERY TRADITION FORWARD

From the first silver arm rings hacked into trade-weight, to the serpent brooches buried with queens, Viking jewellery was never just about beauty. It was magic, oath, and wealth you could wear on your skin. It told the gods you believed, it told your kin where you stood, and it told strangers how far your people had travelled.

At Northern Black, we work in that same spirit. Our pieces are living echoes of those designs — godmasks, serpents, hammers, and coins, all drawn from the artefacts that still speak to us. When we set Yggdrasil in bronze or coil Jörmungandr around your finger, it is with the same intent the old smiths had: to bind story, strength, and meaning into metal.

So choose what speaks to you — the hammer, the serpent, the mask — and wear it as they did: as a prayer, a promise, and a piece of the world made tangible.

Find yours in the Northern Black jewellery collection.